In 2011, the UK Border Agency took part in two mass deportation charter flights to the DRC – 16th February and 28th April.

Frontex, the EU’s joint border agency, organised both flights.

Frontex, the EU’s joint border agency, organised both flights.

On February 16th*, other states putting deportees on the flight were Holland, Belgium, Finland, Ireland and Switzerland. The budget was €329000. (Source: Frontex)

On April 28th, around 20 No Borders activists in Belgium blocked the entrance to the 127 bis detention centre in Steenokkerzeel, near the main airport of Brussels. It was an attempt to stop the deportation of 60 Congolese refugees on the charter flight Kinshasa organised by the joint European border agency Frontex and “secured” by Belgian federal police. The action began at 4.30 am when activists blocked the gates using lock-ons. The Congolese prisoners were due to be taken from the detention centre to a plane waiting at the Melsbroek military airport. More prisoners were being brought from four other countries, including the UK as well as Ireland, Holland and Sweden, to join the flight.

At around 9am the Belgian police cutting team managed to clear the blockade and the activists were arrested. Police closed off the area around the detention centre to prevent access to journalists who had arrived to cover the action. By midday the Congolese prisoners had been taken out of the detention centre by bus under a heavy police escort.

Detailed evidence of the dangers faced by people who are forcibly deported to the DRC can be found here: http://justicefirst.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Unsafe-Return.pdf

*The UKBA used flight number PVT 002 to Kinshasa, departing @ 7:00am

NB: During 2011, European governments e.g. Ireland, have organised other mass deportations to DR Congo without the UK’s involvement.

From Ugandans Blog, FEBRUARY 7, 2011

How could you say that there is no danger in the Congo(DRC), with a recorded 10% reduction in their population in a 6 year period due to an blood Coltan trade that only benefits the cartels and world cell phone users ? Those deported will realize the worst bite of this action, when they come face to face with the pained they had left behind, dependent AIDS orphans, relatives reeling with dashed hopes of having sold all their belongings to cover visa fees and tickets to give a last lease on life to a relative fleeing homeland persecution. [Full article here ]

Britain sending refused Congo asylum seekers back to threat of torture

Refused asylum seekers tell of imprisonment in DRC and violent persecution when they return

By Diane Taylor, Guardian 27 May 2009

Police at Kin Mazière intelligence HQ, Kinshasa, allegedly shown with one of their detainees in 2008, before the arrival of the deportees Rabin Waba Muambi and Nsimba Kumbi. Photograph: Guardian

The British government is sending refused asylum seekers back home, a Guardian investigation has revealed, despite the fears of human rights campaigners and lawyers that deportees could encounter persecution on their return.

The government claims that those forcibly returned will be safe.

There are an estimated 10,000 Congolese asylum seekers in the UK, many of whom are at risk of being forcibly removed. The sending back of such people to the Democratic Republic of the Congo was suspended in 2007 but recently resumed.

The revelations about the possible torture in Congo came as the government intensified its operation to forcibly remove Congolese nationals from the UK. Last Thursday there was a charter flight carrying 24 Congolese bound for Kinshasa, the first such flight for more than two years.

Nsimba Kumbi, 33, a refused asylum seeker, was removed from the UK on 13 March, following detention in the Campsfield immigration removal centre in Oxfordshire. He was then detained in the DRC capital, and taken to the notorious secret police headquarters Kin Mazière, the Kinshasa headquarters of the general directorate of intelligence and special services, where, he says, he was tortured for three weeks.

Kumbi says that during his incarceration he was badly beaten, that he received burns and was forced to give a male guard oral sex while his hands were tied behind his back. He says he is now in so much pain he can only move his neck in one direction. The wounds on his back from beatings are gradually drying. He says that nerve damage means he can barely move his fingers.

Continue reading here

From Sons of Malcolm Blog Spot http://sonsofmalcolm.blogspot.com

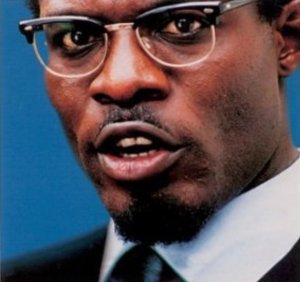

Tribute to Patrice Lumumba on the 50th anniversary of his assassination

Malcolm X, speaking at a rally of the Organisation of Afro-American Unity in 1964, described Patrice Emery Lumumba as “the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent. He didn’t fear anybody. He had those people [the colonialists] so scared they had to kill him. They couldn’t buy him, they couldn’t frighten him, they couldn’t reach him.”

Reading the writing on the wall, the Belgians decided to grant independence much sooner than anybody was expecting, in the hope that they would prevent the further growth of the nationalist movement; that it would be denied the chance to develop a coherent organisational structure and would therefore be heavily reliant on Belgium’s assistance. However, Lumumba had rallied the best elements of the nationalist movement around him and clearly had no intention of capitulating.

At the independence day celebrations on 30 June 1960, Belgian King Baudouin made it perfectly clear that he expected Belgium to have a leading role in determining Congo’s future. In his speech, he chose not to mention such unpleasant moments in history as the murder by Belgian troops of 10 million Congolese in 20 years for failing to meet rubber collection quotas. Instead he advised the Congolese to stay close to their Belgian ‘friends’: “Don’t compromise the future with hasty reforms, and don’t replace the structures that Belgium hands over to you until you are sure you can do better… Don’t be afraid to come to us. We will remain by your side and give you advice.”

He and his cohort were therefore shocked when Lumumba, newly elected as Prime Minister, took the stage and told his countrymen that “no Congolese worthy of the name will ever be able to forget that it is by struggle that we have won [our independence], a struggle waged each and every day, a passionate idealistic struggle, a struggle in which no effort, privation, suffering, or drop of our blood was spared.”

Referring clearly to Belgium, Lumumba stated that “we will count not only on our enormous strength and immense riches but on the assistance of numerous foreign countries whose collaboration we will accept if it is offered freely and with no attempt to impose on us an alien culture of no matter what nature”.

Lumumba, caring nothing for being polite to the Belgian dignitaries in the audience, concluded: “Glory to the fighters for national liberation! Long live independence and African unity! Long live the independent and sovereign Congo!”

Ludo de Witte writes of this historic speech: “Lumumba [spoke] in a language the Congolese thought impossible in the presence of a European, and those few moments of truth feel like a reward for eighty years of domination. For the first time in the history of the country, a Congolese has addressed the nation and set the stage for the reconstruction of Congolese history. By this one act, Lumumba has reinforced the Congolese people’s sense of dignity and self confidence.” (The Assassination of Lumumba)

The Belgians, along with the other colonialist nations, were horrified at Lumumba’s stance. The western press was filled with words of venom aimed at this humble but brilliant man – a man who dared to tell Europe that Africa didn’t need it. The French newspaper ‘La Gauche’ noted that “the press probably did not treat Hitler with as much rage and virulence as they did Patrice Lumumba.”

In the first few months of independence, Belgium and its western allies busied themselves whipping up all kinds of political and regional strife; this led to pro-Belgium armies being set up in the regions of Katanga and Kasai and declaring those regions to be independent states. This was of course a massive blow to the new Congolese state. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the Belgians (along with their friends in France and the US, and with the active support of the UN leadership) developed plans for a coup d’etat that would remove Lumumba from power. This was effected on 14 September, not even three months after independence.

But even under house arrest, Lumumba was a dangerous threat to colonial interests. He was still providing leadership to the masses of Congolese people, and he still had the support of the majority of the army. Therefore the Belgians connived with the CIA and with their Uncle Tom stooges in Congo to murder Lumumba. That Belgium is most responsible for Lumumba’s death is amply proven in Ludo De Witte’s book, The Assassination of Lumumba. Furthermore, the UN leadership was complicit, in the sense that it could very easily have put a stop to this murderous act.

Lumumba, along with three other leading nationalists, was assassinated by firing squad (led by white Belgian officials in the Katangan police force), after several days of beatings and torture.

When the news of Lumumba’s murder broke, there was outrage around the world, especially in Africa and Asia. Demonstrations were organised in dozens of capital cities. In Cairo, thousands of protesters stormed the Belgian embassy, tore down King Baudouin’s portrait and put Lumumba’s up in its place, and then proceeded to burn down the building.

Sadly, with Lumumba and other leading nationalists out of the way, the struggle for Congo’s freedom suffered a severe setback which was not to be reversed for over three decades.

There are a lot of important lessons to learn from this key moment in the history of anti-colonial struggle; lessons that many people have not yet fully taken on board. As Che Guevara said: “We must move forward, striking out tirelessly against imperialism. From all over the world we have to learn lessons which events afford. Lumumba’s murder should be a lesson for all of us.”

To this day, western governments and media organisations use every trick in the book to divide and rule oppressed people, to stir up strife, to create smaller states that can be more easily controlled. To this day, they use character assassination as a means of ‘justifying’ their interventions against third world governments – just look at how they painted Aristide in Haiti, or how they paint Chavez, Castro and many others. To this day, ‘UN intervention’ often means intervention on the side of the oppressors. To this day, the intelligence services use every illegal and dishonest means to destabilise and cause confusion. We all fall for these tricks far too often.

On the bright side, the past decade has been one of historic advances; advances that point the way towards a different and much brighter future. The political, economic, military and cultural dominance of imperialism is starting to wane. As Seumas Milne pointed out at the recent Equality Movement meeting, the war on terror has exposed the limits of western military power. Meanwhile, the economic crisis has started to discredit the entire neoliberal model. The rise of China, the wave of progressive change in Latin America, the emergence of other important third world players – these all indicate a very different future.

In Congo itself, progress is being made, although it often seems frustratingly slow (principally because the west is still sponsoring armies in support of its economic interests). But, as De Witte writes, “the crushing weight of the [Mobutu] dictatorship has been shaken off”. We can’t overstate the importance of this step.

As we all move forward together against imperialism, colonialism and racism, we should keep Lumumba’s legacy in our hearts and minds.

“Neither brutal assaults, nor cruel mistreatment, nor torture have ever led me to beg for mercy, for I prefer to die with my head held high, unshakable faith and the greatest confidence in the destiny of my country rather than live in slavery and contempt for sacred principles. History will one day have its say; it will not be the history taught in the United Nations, Washington, Paris, or Brussels, however, but the history taught in the countries that have rid themselves of colonialism and its puppets. Africa will write its own history and both north and south of the Sahara it will be a history full of glory and dignity … I know that my country, now suffering so much, will be able to defend its independence and its freedom. Long live the Congo! Long live Africa!” (Lumumba’s last letter to his wife, Pauline).

DOCTOR WHO HELPS CONGOLESE RAPE VICTIMS POINTS THE FINGER AT THE ‘WEST’ FOR THEIR ROLE IN CONGO’S OPPRESSION

Deep in the eastern Congo, in the thick of a conflict that plumbs the

depths of human cruelty, one doctor in a single-storey hospital is

keeping hope alive. Gynaecologist Denis Mukwege draws his strength,

he says, from the indomitable spirit of the most weakened of victims

– women raped in a calculated act of war who arrive, “broken, waiting

for death, hiding their faces”, at his hospital. “Often they cannot

talk, walk or eat,” he says.

A 14-year war that is, in effect, a continuation of the genocide that

took place in neighbouring Rwanda has become a “gynocide”, in which

rape is used to tear the bonds of a community apart and facilitate

access to mineral wealth.

In this volatile environment, 55-year-old Mukwege and his team have

surgically repaired more than 20,000 women out of the thousands who

have been war-raped in the Congo’s Great Lakes region. “Rape,” he

says, “destroys women beyond the bounds of the describable.”

Yet his patients keep inspiring him to strengthen his commitment. “A

few years ago, a woman came to us who had been raped and had caught

HIV,” he says. “She arrived with her five children, and we treated

her. When she left, she was given $20 to help her on her way. The

other day she invited me over. She has bought a piece of land, built

a house, paid a dowry for her son’s wedding and has $1,000 she wants

to spend on a business trip abroad. When you see the determination

that can exist within someone whom one has tried to destroy, you want

to fight alongside them.”

Panzi hospital sits on a tree-lined dirt road in a suburb of Bukavu,

the capital of South Kivu province, built by the Belgians to resemble

an Ardennes town. Simple but clean and well organised, the 400-bed

hospital is a haven of sanity in a sick environment. Mukwege built it

up from scratch in 1999 after his previous hospital at Lemera, 300km

away, was destroyed.

Mukwege is tall, his height exaggerated by his black clogs – a

reminder of time he spent in Sweden, where all medical staff wear

them. He has a deep voice, a ready ear and a childlike glint in his

eye whenever things get tense. Pipped to the 2009 Nobel peace prize

by President Obama, he is adored here and faces a barrage of

greetings on his daily rounds.

On his desk, the lamp is vintage Ikea, supplied by the Swedish army.

Mukwege, a pastor’s son who trained in Burundi and France, drew on

his contacts in the Pentecostal church to set up Panzi. “When I was

eight, I accompanied my father to see a little boy who was ill. He

prayed for the boy but, to my disappointment, he did not give him

medicine. He said that was the doctor’s job. So I told him I would

become a doctor so people he prayed for would get better more

quickly.”

The third of nine children, he opted for gynaecology early in his

career after seeing the pain endured in childbirth – especially

forced deliveries due to the lack of availability of Caesarean

sections – by rural Congolese women. He says his faith in God helps

him to confront the depraved notion of rape as a weapon of war in a

conflict where forces on all sides often share one rifle between

three soldiers. “It is the work of Satan. It is evil. In a

conventional war, if someone is killed by a bullet, there can be

grieving and life moves on. With rape, the effects can surface 15

years later.”

He believes the war in eastern Congo – which began in reprisal

against perpetrators of the 1994 Rwandan genocide and has evolved

into a frenzied scramble for mineral wealth, especially for the

prized colombo-tantalite (coltan), crucial for the production of

microchips – has been allowed to continue because of discrimination

by the international community. “The indescribable events here amount

to the worst form of terrorism. In any other part of the world, the

international community would have put a stop to it. International

justice is not doing its work here. There are people in some parts of

the world who believe that other human beings – Africans – somehow

have a higher threshold of pain, that they love their children less,

that savagery for them is normal, or rape culturally acceptable.”

A few hundred metres from the hospital, Mukwege has set up a safe

house where patients, after counselling, are taught sewing, weaving

and soap-making skills. Raped women need to become self-sufficient

because they are often rejected by their husbands and families.

The rape survivors that pass through Dorcas House are aged between

two and 80. One 15-year-old tells her story while struggling to

pacify her 18-month-old son, conceived after she was taken from her

village by armed men and forced to be a “wife” for several months. “I

cannot go back to my village. I am afraid they will take me again. I

heard recently that they took my cousins. I also do not know whether

my aunt, who is my only living relative, would take me in, or accept

Baraka,” says the girl, who, despite having borne a son conceived in

hate, gave him a name that means “blessing”.

Mukwege says sexual assault is comparable to biological warfare as an

extermination tactic. He says there is a policy to make fathers and

children watch the rapes. To render the woman sterile, the rapists

complete the brutality by firing a bullet into the vagina or

shredding its walls using a rifle butt or tree branch.

There are signs that the international community is waking up to this

conflict, which may have claimed as many as four million lives – more

than any other since the second world war. After a frenzied attack in

July in which 300 women were raped over three days in Walikale, in

northern Kivu, the United Nations last month sent a delegation to

investigate. In France, Callixte Mbarushimana, the political leader

of the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR) was

arrested under an International Criminal Court warrant that cites

rape among the charges. But this month, claiming a renewed need to

quell chaos, Rwanda has reportedly rescinded on an agreement made in

September and sent troops back across the border into Kivu’s three

provinces.

Like many in his country, Mukwege believes the international

community would rather have a war-ravaged Congo that can be pillaged

than one that, by its sheer size and natural resources, could become

powerful. “History is repeating itself,” he says. “A century ago, the

world needed rubber for tyres and 10 million people died in King

Leopold’s plantations. Now it wants coltan ore for the microchips of

phones and gadgets, and Congo is home to 70% of reserves.”

On his white coat, a badge given to Mukwege by a Jewish organisation

cries for an end to the cynicism: “Don’t stand idly by,” it says. At

Panzi, the message seems to have filtered down to all. “The other

morning there was a rumour that my house had been attacked. When I

arrived at the hospital, I saw three handicapped girls whom I knew

because they are patients, waiting for me.

“The teenagers started hugging me and saying they had heard that my

life was in danger. They explained that they had come to defend me. I

had tears in my eyes. These handicapped girls wanted to help me, a

big burly man. This is what I feel all the time from those who come

to the hospital – the desire to keep loving, to keep giving, even

when someone has tried to strip you of all your dignity and values.

You cannot abandon people like that.”

Excellent website

Detailed evidence of the dangers faced by people who are forcibly deported to the DRC can be found here: http://justicefirst.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Unsafe-Return.pdf

My brother today refused to go on a flight to angola because he doesn’t know that country he came here when he was 8yrs old his now 29 we’ve been here over 20 years because he refused to go on the flight they badly beat him stamping on his whole body, on his head his now bleeding from his hands,can’t swollow,his necks swollen because they also strangled him his badly bruised all over his body he can barely speak now because of what they’ve done to him and this isn’t the 1st time its happened at least 3times but this times the worst if anyone is reading this and can help please email me a contact number as this behaviour is not on the country claims to go by the law but yet again the guards are beating people for not broading their flights this is disgusting behaviour and britain should be ashamed of themselves for not looking into these cases I’m so disgusted

Hi Isabelle,

I’m so sorry to hear what happened to your brother. I’ve sent you an email privately with more advice. In general, if someone you know is assaulted during a deportation from the UK, I suggest they contact an organisation like Medical Justice who can help get them seen by an independent doctor. http://www.medicaljustice.org.uk